Robin Lane performing with The Chartbusters at Tyngsboro Country Club, 1982

Singer-songwriter-mentor-performer-mother-philanthropist-healer: meet my beautiful friend, rock icon Robin Lane. Like many aspiring female rockers, I sat glued to MTV ( when it was actually about music) waiting for my favorite videos. One of theses was by Robin Lane & The Chartbusters—their big song, “When Things Go Wrong.” Years later Robin still writes, sings, and performs. She also dedicates much of her time to supporting people when things go wrong in their lives. Her nonprofit organization, Songbird Sings, uses songwriting and music to mentor people who have been through difficult experiences, such as sexual abuse, domestic violence, and human trafficking.

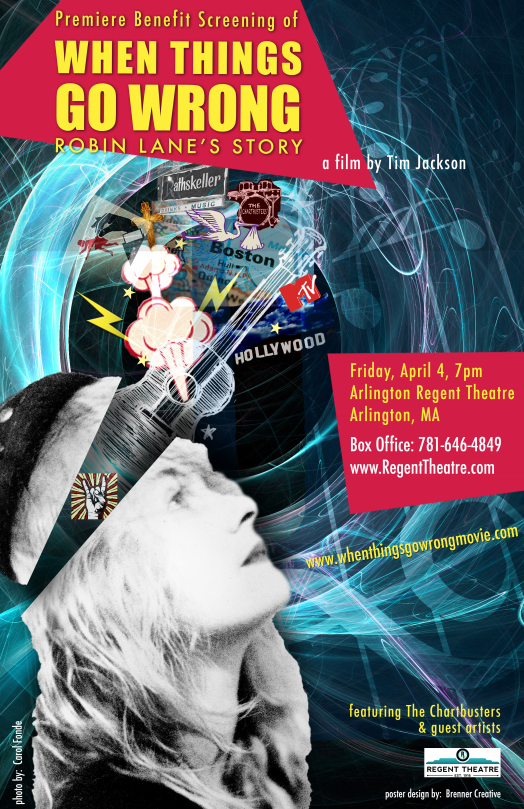

Now Robin Lane’s life story is about to come to the big screen, in a new film by Tim Jackson—named after the big song—and we are very pleased to have Larry Katz interview Robin just a few days before the movie premiere and benefit this Friday, April 4, at the Regent Theater in Arlington, MA.

“When Things Go Wrong,” the new film about Robin Lane, includes all the elements you expect to find in the story of a rock musician’s life.

“When Things Go Wrong,” the new film about Robin Lane, includes all the elements you expect to find in the story of a rock musician’s life.

Troubled childhood? Check.

Wild teen years? Check.

A shot at stardom with a major label record deal? Check.

The band’s breakup and the hard times that inevitably follow? Double check.

It’s all there in “When Things Go Wrong,” a new film which will be seen for the first time on Friday, April 4 at 7 p.m. at the Regent Theater in Arlington, MA, a premiere benefit screening that will include a live performance by Lane and her former band, the Chartbusters.

But—spoiler alert—the movie does not end with either the rehab stint or triumphant comeback found in your typical “Behind the Music”-style rock doc. These days Lane, the queen of the Boston new wave scene circa 1980, has found a new venue for her voice and guitar: leading songwriting workshops as a way to help victims of sexual and domestic abuse, at-risk teenagers, prison inmates, and the elderly.

While what Lane does in her workshops is a form of music therapy, she is quick to point out that she is neither a therapist nor a counselor.

“I’m a facilitator,” she said from her rural home in Western Massachusetts. “I facilitate these situations where people can, through songwriting, find a key out of their dilemma—a key to their own healing capabilities. My role is really just to help them find a way to write a song, to help them to heal themselves and get out of whatever they’re in that’s dangerous and not good for their lives.”

It’s not a job she consciously pursued, at least not at first, but it’s one that Lane has found herself eminently well-qualified for. Music, after all, had always been her own lifeline.

“I’d been writing songs for years,” she said, “and didn’t realize why. I’d always loved music, but if I hadn’t had songwriting I would be scared to think of what would have happened to me.”

Lane’s life story has more than its share of mental and physical hurt. Distant parents. Sexual assault. Domestic violence. Divorce. And a tantalizingly close, ultimately frustrating brush with stardom. When the first two Robin Lane and the Chartbusters albums failed to sell as much as expected, the band was tossed aside by their label, Warner Brothers. And after Lane gave birth to a daughter, Evangeline, she found she was no longer considered a serious contender in the male chauvinist rock world of the 1980s.

“I raised my child,” Lane said of her post-Chartbusters years. “Got married again. Had a couple of dogs. Played around. Made the ‘Catbird’ CD [ed. 1995]. Then I got divorced, around 1999.”

And almost without realizing it, she was embarking on a new career as a songwriting mentor.

“I had been working with young kids at the camp my daughter went to in Maine,” Lane recalled. “I would get them to write lyrics and I would put their lyrics into songs. Then I worked with some teenagers when my daughter was in school in Cambridge. But after I got divorced and moved out to Western Massachusetts, I was pretty shut down from the divorce. I came upon this place in this little town, Turners Falls, called the Women’s Resource Center. I walked in and they were doing this writers group and they asked me if I wanted to be in it. I sat down and started doing that. Then they found out that I write songs and several people knew who I was. So they said, ‘Why don’t you teach us how to write songs?’

“I didn’t really know that these women had had traumas in their lives. I kind of did, but I didn’t even know that you called it trauma. I didn’t know much about anything except that I did have that kind of stuff in my own life from when I was growing up and then from other relationships. So I identified with these women. It turned out it was a center for women who needed to heal from domestic violence and childhood abuse, mental health issues, addictions.

“I fell into it leading these songwriting workshops because I’m a songwriter and I happened to be with these people that wanted to learn how to write songs. They had all this trauma in their lives. The stories were so awful that I was amazed that these women were still functioning. But the songwriting really helped them. In fact it helped them a lot more than traditional therapy. They just started getting better and better.

“I also started realizing that I had some things that I really needed to heal from. And as I started teaching these songwriting workshops and I heard these women reveal themselves in their lyric, I started coming to terms with my own issues that needed to be healed more.”

Lane established her program, A Woman’s Voice, in 2002. She also launched Giving Youth a Voice, a songwriting program for inner city kids and teens.

Working with sexually exploited young women from Roxbury was a particular challenge.

“I’m not a confident person,” Lane said. “But once I start doing things and I know that they work, then I get some confidence. At first I didn’t put it all together that these girls had been trafficked. I knew they had been through some heavy stuff, but they just looked like teenaged girls. When I started with them there were a lot of cold eyes. I got the looks.

“But that doesn’t really bother me because I raised a daughter!” Lane laughed. “It’s par for the course with teenagers. These girls were quite resistant at first. They were resistant to this woman coming in and trying to get them to write songs. But by the second day they were really getting into it because they were writing what they really wanted to write. They start getting it and going deeper into themselves. And when I set up the portable recording studio for them, they go crazy. An amazing transformation happens. They’ve written amazing songs with incredible lyrics, usually in rap style, although rap music is not my forte. But I get to have fun trying to make it work. That’s where my confidence comes in. I know I can be funny and have fun. That’s what I rely on.”

After honing her songwriting workshop skills for more than a decade, Lane is determined to expand the use of her methods through the non-profit she founded, Songbird Sings.

“I want it to grow,” she said. “I’d love to have enough money for Songbird Sings so each year I can go and work in places where there are people in need and nobody has to pay. I also want to have a place where I can teach the teachers so there will be more people doing songwriting workshops. And that takes money.”

Maybe, it is suggested, “When Things Go Wrong” will bring needed attention to the work Lane is doing.

“I hope so,” she said. “We need more visibility.”

But “When Things Go Wrong” needs financial support too. Filmmaker Tim Jackson—Lane’s longtime friend and, not coincidentally, the Chartbusters’ drummer—started the project in 2007 and is still short of funding. Hence the benefit premiere in Arlington.

“I don’t think Tim thought it would take this long to get this film done,” Lane said with a laugh. “The whole problem is that it’s not like a big major film where there’s tons of money. He had to do a Kickstarter campaign and find money from other sources. The screening in Arlington is a benefit to raise even more money so that he can pay for some of the things in the film—like the right to be able to use my songs and stuff like that.”

Sad to say, like too many other musicians, Robin Lane does not own the rights to her own songs.

“They belong to the publisher,” she said. “All of the songs that are in the movie are not the versions that were on our Warner Brothers records, they’re other versions. But the publisher owns the copyright. Don’t get me going on that one. It’s just so unfair!”

Maybe there are a few things Lane wishes she had done differently. But she wouldn’t trade the work she does today for her rock dreams of yesteryear.

“I think before music had always been about me,” she said. “It had nothing to do with anyone else, except getting an audience to like my songs. It felt really good, but now it’s about all these other people who change and transform through writing songs, something I’ve been doing all my life. This feels better. I’m helping people. Now it’s not just about me. It’s bigger than me.”

About the Author

Former Boston Herald columnist and editor Larry Katz has covered music and the arts for more than 30 years. Visit his website, thekatztapes.com. Contact him at larry@thekatztapes.com.